Richard

Bell

Artist

Biography

Richard

Bell is a Queensland urban artist and political activist; openly

discussing the history of race relations through video works of

Scratch

an aussie(Figure

2) and Uz

vs THEM

(Figure 3); Scientia

E Metaphysica(Figure

4) and Bell's Theorem focuses on the state of aboriginal art industry

and the art market; and in The

Peckin Order

(Figure 1), Bell appropriates the western pop art stylisation of Roy

Lichtenstein to open dialogue regarding indigenous cultural

appropriation;

Richard

Bell's experiences during his youth in an openly racist australia and

exposure to political activism in the 1970s are the roots of his arts

practice. In 1953 indigenous people were not permitted to shop in the

town Charleville (Queensland) where he was born. Living off the land,

his family constructed a shack once they had collected enough

discarded tin, and had previously raised bell for the first two years

of his life in a tent (Allas 2008).

Bells

mother moved his brother Marshall and himself from Queensland to the

Northern territory in 1959. It is here that she began working at the

Retta Dixon Home in Darwin. The original intention of the Retta Dixon

Home was to assist the assimilation of aboriginal children into

western culture and in the process undermined aboriginal groups.

Between the 1860s and 1970s approximately 50,000 Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander indigenous children were removed from their

families and communities, these children are contemporarily known as

the 'Stolen Generations' (Bambrick 2011).

At

the age of 17 Bell's mother passed away and he was fostered by Nellie

and Harold Leedie in Bowenville. It is interesting to note that

Nellie Leedie is a relative of renowned Aboriginal activist “Sugar”

Ray Robinson. He left school in year twelve to persue an

apprenticeship in Dalby with Napier Brothers as a toolmaker, where he

stayed for two years before heading fruit picking in tasmania and

victoria (Allas 2008). He found himself in Redfern, Sydney later

that same year in 1974 . It is here that he become associated with

Redfern community and Black Panther-inspired politics of the 1970s

which defined many of his peers indigenous identity (Harford 2013).

Bell

relocated to Toowoombah after living in Sydney for ten years, then

onto Moree with his partner, Liz Duncan. Now with a family of three

children they moved to Brisbane to join his brother in creating

artefacts, such as boomerangs, for the international tourist market

which they sold from their shop 'Wiumulli' (1987 to 1990). Bell

continued working as a 'tourist artist' till 1994, making postcard

style prints that were mounted and shrink-wrapped and crafting

boomerangs which were distributed throughout tourist retail outlets

such as Queensland and New South Wales tourist information centres.

During this time he also begain to be exhibited in 'fine art'

exhibitions such as the show 'Balance 1990'.

Bells

life took a major turn, his relationship broke down, and from 1998

until 2000 he lived the life of an iterant moving between Moree,

Kempsey and Redfern. Whilst in Redfern during the 2000 Sydney

Olympics Bell was invited to attend the art opening at the Museum of

Contemporary Art (Sydney) of the late artist “Urban Dingo” by

Tiriki Onus ( Lin Onus 's son). Prior to the exhibition

opening Bell opened dialogue with Onus and Michael Eather regarding

politics and art. “i was told that I could do and say anything and

not get arrested” (Richard Bell 2014). This experience changed the

course of Bell's artistic career and led to him revisiting his

previous bodies of work.

Following

the exhibition Bell was invited by Eather for the following year to

work at the Fireworks Gallery. During his time there he feverishly

experimented over twelve hours a day with different techniques and

aesthetics which would aid the message he wished to deliver.

To

further develop his practice he began researching contemporary art

material, in particular the writings of Imants Tillers and other

writings on Tillers. Inspired he reproduced Tillers’ work Untitled

(1978), which is itself a reproduction of a Hans Heyson work, Summer

(1909) which he stated that he “pulled the black-fulla act on

Tillers” (Bell 2014) .

In

2002 Bell was given the opportunity to exhibit alongside the works of

Emily Kngwarreye, Michael Nelson Jagamarra and Imants Tillers in the

exhibition “Discomfort” at Fireworks Gallery. Along side the

installation piece for this show he presented his renowned 12 page

'Bell's

Theorem' (Allas 2008).

'Bell’s

Theorem' is significant as its manifesto highlights some of the

inequities in the Aboriginal Art market which have been

long-standing. And notes that it is non-Aboriginal people, not the

aboriginal people, who define and control the Aboriginal Art market.

'White people say what’s good. White people say what’s bad. White people buy it. White people sell it.’ Richard Bell 2007.

Since

the emergence of the international aboriginal art market in the 1980s

approximately 50% of australian artists are indigenous and are

recognised as the largest producers of art per capita (Neale

2010).

It is the belief of Bell that western culture is in the process of

slowly digesting and commodifying aboriginal culture (Perkins 2014).

Within

the Western art system, Australian Aboriginal art defines indigenous

artists as either traditional, people living in the 'outback', or as

'Urban'. Traditional Aboriginal art refers to artworks that

aesthetically empoly imagery and styles used in or relating to

designs that engage with themes such as ancient traditions and

ceremony. Bell adds that these works are fair game for appropriation.

Aboriginal artists that live in built up residential areas such as

towns and cities and express contemporary themes and engage with

western media and style are described as 'Urban'. Bell notes that

this term errodes cultural authenticity through the process of

colonisation (Chapman 2006).

Speaking

as a member of the Jiman Kamilaroi, Gurang Gurang and Kooma

communities (MCA 2017).

Bell states, ‘ … Our culture was ripped from us and not much remains. Most of our languages have disappeared. We don’t have black or even dark skin. We don’t take shit from you.’

In

2003 the philosophical grounding in 'Bell's Theorum' led to a group

of Brisbane-based Aboriginal artists, including Bell, Tony Albert,

Gordon Hookey and Vernon Ah Kee, to form the radical collective

proppaNOW (Perkins 2014).

'Bell's

Theorum' accompanied his painting Scientia

E Metaphysica

which was entered into the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander Art Awards at the Museum and Art Gallery of the

Northern Territory in 2003. The painting emblazoned with the words

'Aboriginal Art / It's A White thing', a bold statement expressing

his opposition to the commercial use in advertising campaigns and

tourist promotion of Aboriginal imagery. This conceptual exploration

is additionally expressed in his appropriation of Western Modernism's

painterly expression and iconography, styles and forms.

Scientia

E Metaphysica aesthetically

is an evolved Indigenous expression of colorful and gridded patterns

reminiscent of Pop art. The issues in the sociopolitical history of

black and white relations in Australia are expressed through a

concise visual formula of black and white dripping and fields of the

same colors on opposing sides of the painting. To futher the

discourse of aboriginal art exploitation at the hands of art dealers

and middle men, a left biased abstract red triangle is making

reference to the 'triangle of discomfort', a concept intruduced in

'Bell's Theorum' (GCA 2017).

Scientia

E Metaphysica went

on to

win the prestigious prize commonly known as the 'telstras'. Bell

received national recognition from the contemporary art world as an

artist who's practice carried a relevant and conceptually strong

message and said it loudly (Allas 2008).

The

dialogue between indigenous and white australians is continued in his

video work Uz

vs THEM

.

“This artwork examines and challenges existing sociopolitical power structures. Depicting a cool, calm, collected black man against an angry white villain, it presents no apprent winner.” Richard Bell, 2007 (MCA 2017).

The

two fighters training at a boxing gym in Richard Bell’s video

work Uz

vs Them

provides the environment for the transposition of the political

struggle between Aboriginal and white Australia. Bell takes on the

role of the ‘magnificent black hero’ ready to ‘fight for

Australia’, the other ‘an angry white dude’. The two men are

training to defending opposing ideological stances.

The

posturing of the two men in Uz

and Them conveyed

with a tongue-in-cheek approach, with Bell surrounded by a posse of

gyrating white girls while he is wearing a suit.

Employing

Bell's signature sarcasm and humour the verbal and physical sparring

match between the two, while grappling with serious and confronting

issues, never takes itself too seriously. By confronting white

Australians with their position in the history of racial politics and

drawing on popular culture references such as urban Indigenous music

and vernacular language, Uz

vs Them reverses

power relations (MCA 2017).

Bell

again uses video at an almost cinematic scale to reverse power

relations in Scratch

an aussie. Bell

states:

''For a video installation I wanted to create stereotypical Australians, the beautiful, blonde Aryan-looking ones, and they also refer to the beach and the Cronulla riots, ...I put them in bikinis and budgie smugglers. Then I added two black men in intellectual positions, which you never see on TV.'' Richard Bell, 2013.

In

this video work Bell casts himself in a dualistic role of therapist

and patient. As the role of the therapist his patients are blond,

gold swim-suited Anglo-Australian whom devulge trivial middle-class

first world concerns, rants and racist jokes.

In

the next sequence Bell is now patient to his long-time collaborator

Gary Foley. It is not the belittlement or pain, but the abject

absurdity of those who flaunt it that he expresses. He is laughing

at, not with, his budgie-smuggling and bikini-clad blond subjects

(Rule 2013). And in a strange twist, the golden bikini, reminiscent

of the Surfers Paradise Meter Maids, now sits in the pantheon of

Australian art, thanks to Richard Bell (Harford, 2013).

Bell

argues that white Australia has not only appropriated Aboriginal land

but also its traditional art. And uses it to strengthen Australia's

tourism and image, all the while the government hides the poverty,

lack of roads, education and schools, and the racist attitude that is

part of aboriginal life (Branrick 2011). In response to this Bell

engages with appropriation and manipulation of a range of western art

genres in his art and paintings.

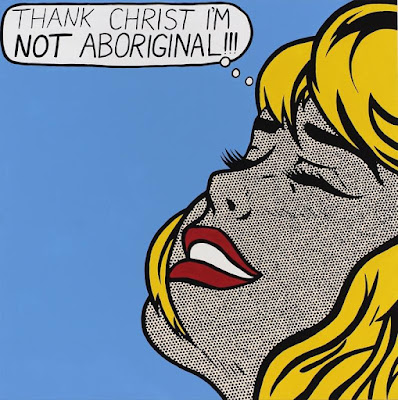

Roy

Lichtenstein’s melodramatic comic strip parody has been

appropriated in Bells 2007 paint The

Peckin Order

which is part of a series of paintings called Made Men. The original

painting by Lichenstein, titled

Shipboard Girl, depicts

a blonde woman, eyes closed and red lips slightly parted, throwing

her head back against the left side of the canvas. The blonde in

Shipboard

Girl is

replicated in the The

Pecking Order ,

Bell alters her skin tone to black, laying her to the right side of

the canvas and has added a thought bubble, “Thank Christ I’m not

Aboriginal!!!”, and in doing so is reversing expectations (Bambrick

2011).

Richard

Bell’s artistic career now spans three decades and has garnered

financial and critical success. His solo exhibitions include Richard

Bell: Imagining Victory, Artspace, Sydney (2013); Imagining Victory;

Embassy, Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, Perth (2014); Uz

vs Them, was a touring exhibition organised by the American

Federation of the Arts, and toured to venues across North America

throughout 2013; Exhibition titled, I am not sorry, was held at

Location One, New York. He has also exhibited in numerous national

and international group exhibitions. Bell's works are now held in

the collections of the National Gallery of Australia, Canada, Ottawa,

Canberra and state and regional galleries throughout Australia (MCA

2017).

Richard

Bell's early life, in the openly racist australia of the 1950s, acts

as a cornerstone to his art . His art is provocative, political and

his persona is integral to his arts practice, making Bell inseparable

from his art.

Bell

has appropriated the works of Roy Lichtenstein in The

Peckin Order

(Figure 4) to reverse expectations; discussed the history of race

relations through video works of Scratch

an aussie(Figure

2) and Uz

vs THEM

(Figure 1). Tho while critiquing the Aboriginal Art market in

Scientia

E Metaphysica(Figure

3) and Bell's

Theorem

, the art world has served Bell's political purposes well.

“you can get away with things...you can say virtually whatever you want...and you wont get arrested” Richard Bell 2014 (Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa 2014).

Figure

1.

Richard

Bell, The

Peckin Order

2007, acrylic on canvas 150 x 150cm.

Source:

Milani Gallery. Accessed 10 May.

http://www.milanigallery.com.au/artwork/peckin-order

Figure

2.

Richard Bell, Scratch

an aussie

2008, video, 10 minutes.

Source:

QAGOMA. 2013. Accessed 10 May.

http://tv.qagoma.qld.gov.au/2014/02/25/richard-bell-scratch-an-aussie/

Figure

3.

Richard

Bell, Uz

vs THEM 2014,

video, 2min 47s.

Source:

MCA. Accessed 1O May. https://www.mca.com.au/collection/work/2008.43/

Figure

4.

Richard

Bell, Scientia

E Metaphysica (Bell's Theorem)

2003, acrylic on canvas 240 x 540cm.

Source:

Kooriweb, Accessed 10 May.

http://www.kooriweb.org/bell/aaiawt1.jpg

List

of References

Allas,

Tess. 2008. “Richard Bell“ Design

& art australia online.

Accessed 10 May 2017

Url:https://www.daao.org.au/bio/richard-bell/biography/

Bambrick,

Gail. 2011. “The Art of Confrontation“ Tuffs

Now. Accessed

May 10 2017. url: http://now.tufts.edu/articles/art-confrontation

Bell,

Richard. 2002. “Bell's Theorem: ABORIGINAL ART-It's a white

thing!“ kooriweb

Accessed 10 May

2017. url:http://www.kooriweb.org/foley/great/art/bell.html

Chapman,

Katrina. 2006. “Positioning urban Aboriginal art in the Australian

Indigenous art market“ Asia

Pacific Journal of Arts and Cultural Management. 4(2):

219:228. url: http://apjacm.arts.unimelb.edu.au/article/view/47/38

GCA.

2017. “Scientia E Metaphysica (Bell’s Theorem), 2003“ The

Global Contemporary Art World After 1989. Accessed

10 May 2017. url:

http://www.global-contemporary.de/en/artists/95-richard-bell

Harford,

Sonia. 2013. “Sinister truth behind the bikini“ The

Sydney Morning Herald. Accessed

May 10 2017.

url:http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/art-and-design/sinister-truth-behind-the-bikini-20130205-2dwdb.html

Neale,

Margo. 2010. “Learning to be a proppa“ Aboriginal artists

collective ProppaNOW“ Artlink

30(1).

url:https://www.artlink.com.au/articles/3359/learning-to-be-proppa-aboriginal-artists-collecti/

Perkins,

Hetti. 2014. Tradition

Today : Indigenous Art in Australia from the Collection of the Art

Gallery of New South Wales.

Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales

Rule,

Dan. 2013. “Agitation, Ediquette and Identity: THE ART OF RICHARD

BELL“ . Broadsheet.

Url:

https://www.broadsheet.com.au/melbourne/art-and-design/article/agitation-etiquette-and-identity-art-richard-bell

stateliraryqld

2011. Richard

Bell Digital Story (video)(Youtube:State

Library of Queensland. 2011)

url:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bKB1BezX1CU

MCA.

2017. “Richard Bell: Uz vs Them 2006“ Museum

of Contemporary Art. Accessed

10 May 2017. url: https://www.mca.com.au/collection/work/2008.43/

Museum

of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa 2014. Appropriation,

Modernism and Indigenous Art in the Contemporary Field (video)(

Youtube: Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. 2014 )

url:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IarSaWxwjdE

No comments:

Post a Comment