Artist Interview : Madeleine Grant

Madeleine Grant

Acrobat, aerialist, clown, printmaker, painter, and someone who constantly runs into doors instead of through them – roll up and meet Madeleine Grant, the centrepiece of this circus show. On the training mat of the high-ceilinged room of circus apparatuses and first aid kits at Vulcana Women’s Circus, we chat about the bones of an arts career.

Tristan Griffin, Elijah Jackson & Alexander Wright

Tristan Griffin, Elijah Jackson & Alexander Wright

As a fairly established performing artist in Brisbane, it seems crucial to ask: How and when did you first become interested in the arts – not just performing, but any kind of arts?

I started art school in 1992, just after my 18th birthday, and then was kind of working in Sydney at art school, we did guerrilla art shows as well, we did a few Warehouse break-ins… where we would do installation work and stuff like that too.

I did a double major in visual arts and printmaking but I was also simultaneously working with a physical theatre and performance company… we did absurd stuff… we had an industrial flamethrower, I don't where it came from, and we used to make big puppets. Once I dressed as a profiterole and danced through Sydney for a Fringe Festival [i.e., a festival that showcases works from small companies, generally of an experimental or unconventional nature] … So, it's been a kind of long-term passion.

So, you’ve been interested in installation work. Can you expand on that and how that influences your career now?

I guess it was an indication of my future in clowning… I did one [installation work] in a warehouse where I made a lot of recordings of news stories about children trapped in wells and disappearing in old buildings and then I ran around dressed like a small boy bouncing a ball and sort of darted behind everyone. It sort of worked… in retrospect.

I also made an installation about the Oklahoma bombing once where I filled the space with fertilizer and played the soundtrack for the musical Oklahoma over and over again. In retrospect, I don’t know if any of my ideas were particularly good.

How did your career develop after art school?

I kept working in Fringe theatre; I did Sydney Fringe, Melbourne Fringe, Canberra Fringe Festival for a few years with a company called Odd Productions. Eventually that petered out and then I was exhibiting as a printmaker and occasionally doing kind of random puppetry stuff, really weird stuff, but over time for a while it became less and less. I was working more as a chef in Sydney to pay my rent because it's very expensive and had less time for arts practice. It kind of become, for a while, I would say a career on hiatus.

As you say, rent is expensive. Now in your career, where do you find your main source of income from to survive as an artist?

I manage a library 4 days a week which I’m trying to get down to 3 days a week; it provides me with the ability to train, to buy props, and support my arts practice, and luckily, it's flexible enough that I'm able to be [at the circus] generally.

Is it a goal to have like your arts career to be how you make a living solely?

I think it used to be but honestly, I like the parts of my brain that my other job uses, I like the people that it forces me to interact with, the research work I do… All I wanted for a long time was a career only in the Arts but now…

I want to keep being an arts practitioner and it would be nice to earn enough to maybe only do something else 2 days a week but I don't think I'll ever stop that [other job] now.

It gives me ideas as well, the more different parts of the world I'm able to interact with, the more influences and ideas that I have coming in… I know for me when I was at art school and after art school and working in a small arts community, I got a much narrower focus, which I think can be a problem.

How do you feel about the commercial side of things in your career?

I did [have commercial goals] when I was at school, I had a level of success - my work went to Canada and interstate, I won a couple of prizes and I sold a bit of stuff. Then my work got more radical and I became disillusioned, I remember doing Professional Practice [course in university] and becoming more and more disillusioned with the way that the artworld essentially works and the way that it's necessary to sell yourself. The concept of having a CV and going through a terrifying job interview process, I know it's necessary if you want to sell work and survive, but it seemed so anathema to the process of creation that I really struggled with it.

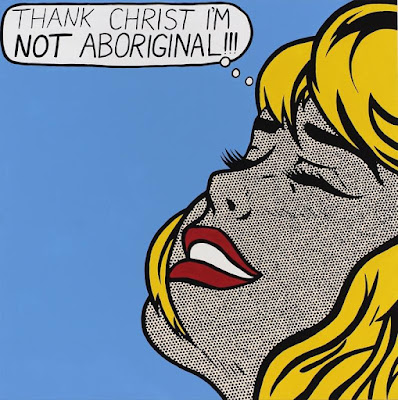

You were described as having “radical left” political views in your online bio…could you tell us what they are and how they influence your career and performances?

It influences everything I do …my dad is a Maoist, I am not, but I was raised by socialists, when I was a kid, we would take car trips through the USSR to learn about socialism… my leanings would be Agrarian Socialism, and it influences everything I do - it influences the way I look at society, with the media. I accept that I live in a capitalist society, I'm a part of that and I try to work in it, but I also try to make art that is in line with my beliefs, so I avoid companies and things I don't agree with and shout at the TV a lot when it gets hard [laughs].

So, when you work with companies, how do these views affect your professional relationships?

Basically I won’t work with companies whose views are in opposition to mine.

For the most part, my personal presentation and the biographies you find online and in my work would probably scare most people away that would potentially be in opposition to me, so it’s not really an issue

How do you apply these views in your performance works?

I try to but I don't think when you do physical work that they are easy to portray… there’s some powerful works in the last couple of years that people have done with successfully combining beautiful circus work with politics but… I don't think I’ve found a way… yet.

So, you work with multiple different institutes, can you explain why you work with each of them?

I work with Vulcana, it's a community-based organisation, it's very supportive and I feel like it has enabled me to be braver in my arts practice. I work with the director Celia [White] and all other people here have helped me to really push what I do, work out how to self-edit, understand how to do better, not just kind of spew it all out onto the stage or onto a piece of paper.

I trained at Circa before that but that was purely kind of grunt work, lots of physical strength focus instead of performance.

Commonthread is our new company, so that's me and three friends working together and that's a new adventure… but other than that it's been mainly solo stuff… I do work [mainly] with another circus performer Elisa, we have an awful lot of ideas, in fact we have 3 shows worth of ideas, but… they’re currently unrealised.

I've worked with Ruckus Slam and… for the West End Festival, I’ve worked with many different companies but generally that's been applying as a solo artist, so these relationships have generally been fairly short lived.

How did your physical practice become centred on circus?

When I was a kid I did gymnastics and I also did a lot of summer holiday clowning kind of stuff in summer camps - you know, your parents go to work, so they send you somewhere every day for a week, those things. Every summer I did circus stuff in Canberra and then when I was 35, not long after I moved to Brisbane, I just kind of decided I wanted to join the circus. It seemed like a good way to get fit and for a few years it was kind of just that [fitness centred] before I started to drift back into actually wanting to perform and… actually seeing the correlation between that and the previous stuff that I've done, realising that physical theatre and circus maybe do have a link… it’s very interesting.

Did you find your previous main way of work [i.e., printmaking and painting] have influenced your performance works? Did these two arts practices converge or remain separate?

The content was always similar, there was always political content and always kind of social commentary but…

I think the access to printing presses disappeared after art school so I was painting for a while and printing become very difficult, but the performance definitely took over… so I still paint and print but it's become secondary to my physical practice

How do you think your arts practice has developed from art school until now? Are there any elements that remain the same or different?

I think everything I did was absurd and everything I do now is absurd …conceptually, I think concept-wise there's a timeline there. The interesting thing is I think I always start off with these grand political statements of these ideas about social justice and then I end up tied to a piece of elastic fighting with a box on the other side of the room, so I think actually what I realised over time is conceptually, I realised that I can work without having to have such a punch you in the face message perhaps. So that maybe the arts practice can stand alone without hiding behind some kind of theoretical framework.

Relating to the comment about the box… On the Commonthread website, you say you are in an “ongoing war with inanimate objects that seem intent on tripping you up” … Can you expand on that and how important this might be to your arts practice?

I did a piece last year where I crossed the room without touching the floor with 9 hand balance blocks and a red chair as the objects used to cross the floor with but not in a very logical way.

And then I’ve ended up trying to put a piece of furniture, that is the chair, together which is in a box …and now I'm working on a ballet on a spinning office chair… And I also put on an entire suitcase of clothes and wrestled with a beach ball last year for a show. So, the point I’m making is somehow I keep ending up with furniture.

What do you think is influencing that?

I suppose, honestly, at the core of it is the idea of the difficulty of everyday life.

Like, I frequently try to walk through doors and miss… it’s that kind of frustration that I feel, and that I'm assuming everyone else does though I could be wrong, with attempting to perform a seemingly simple task and how wrong it can go - that is to me the most difficult route to solve the simplest problem. Almost the idea that everything is acting against you but obviously to the outside observer it's your stupid decision making which is causing this problem. That’s what I like to showcase in my performances and its absurdity.

So that’s definitely a thread for your clowning performances, does that also tie into cabaret or other works you do?

Yes, so the next show that I'm working on, there will be furniture fights but I will also be doing acrobatic work with a lot of people on top of me… There will be aerial work and I'm also going to do a reverse striptease with 100 different pieces of Spanx underwear… So again, having an argument with a seemingly simple apparently helpful object. But with other elements of circus involved.

Could you tell us a bit more about your next show?

It’s called The Resting Bitchface, which is a show with Commonthread… so it hasn't officially been announced by the festival we are in yet, that happens hopefully next week and then we’ll start flying blimps over the city with our name on them [laughs].

Nowadays we don’t fly blimps anymore! Advertisement has become an Internet game. How have you managed over your career in the arts, in terms of having an online presence?

We opened a Hotmail account in 1995 for Odd Productions and we were cutting edge at the time… We used to go to Kinko’s and use the computer and send emails to three other people who had Hotmail accounts… So, there’s a whole period of my arts career which doesn't really exist online which is interesting.

[A lot of what I do isn’t documented] …I think with the timing of some of the stuff that I do… When you see it second hand it's very diluted, it loses something some of its power. It's very difficult to perform something to a camera the same as an audience.

Plus, if I’m getting ready for the show the last thing on my mind is that I need someone to document it and then afterwards I go, oh, that’s another undocumented work of mine…

It seems that a lot of your work is very ephemeral, how would you respond to that?

I think that goes back to our warehouse break ins… A lot of the time the work would stay there, it would get destroyed, things would get burnt down, you'd come back in and some kids have broken in and trashed everything before the opening… so it gave me this attitude to my work that you can do it and walk away.

My graduation piece – which I guess was the height of my arts education - resulted in a fire … post- Oklahoma bombing piece I became obsessed with terrorism …this was 1995 so nobody cared, I printed all these lithographs, all these matchboxes with different riot slogans, and historical terrorists…

I got several buckets of the matchboxes with slogans on them and put a single match in each one and everyone who entered the grad show got one match and a riot slogan… and eventually someone set fire to the six-foot-high pile of matches… The print lecturer [was not] supportive of my scheme, he didn't think that anyone would do that [set the fire], but somebody did. He also made like a masking tape kind of police line and stood behind it waving a fire extinguisher and no one was allowed into my installation.

Anyway, it came to the end of the week and I have one of each of the match books Ive printed in a folio somewhere and the rest just got swept up and put in the bin…

I understand that narrative is incredibly important to your work… Can you expand on that?

What I do, there must be a beginning, a middle, and an end… I have in some ways a very traditional outlook about physical comedy [what I’m working with now]. It must have a story or a Journey to engage with. And if there's not I try and build one into it in my head. Some of the clowning stuff I do in shows, there isn't a narrative, but I've created a narrative structure for myself because it makes it easier for me to perform.

With work like this, and with performance work, conservation is a major issue. A lot of value and commercial success is weighted on the ability to conserve your art and have it last. What do you think about that in relation to your practice?

I think it's great if your art can be conserved. My partner is an artist as well and his work honestly to me is more deserving of conserving, I don't think it's worth any more or less value than mine but it's different.

I reinvent something rather than conserve it… I feel very passionately about Conservation and archiving but not so much about my own stuff.

Some work lends itself to being conserved, and some does not. I think with my work, especially doing clowning. Say, when people are laughing and the timing is good and it's happening, the high that I get and the high they get from the experience, I can't capture that so if I can do it again, if I could improve it, that's great, but it can’t be conserved – in videos, it just looks weird and dry.

I know one of your more recent group shows received some negative reviews and feedback… How do you deal with this inevitable side of an arts career?

It’s necessary sometimes to take them on board. It can be hard when they’re negative and single your character out but it's also bad when there's a positive review and they don't single your character out. They haven't had a huge influence on me… but even with the bad ones, when they're written by people who see a lot of circus shows, a lot of theatre, sometimes even within that negativity they'll be points that can be worth considering.

Negative reviews are definitely a cause of anxiety, but what about the nerves before a performance? How do you deal with that?

When I am performing, I’ll be a little crazy in the hours before. I'll needlessly pack and unpack large bags full of objects I probably shouldn't have brought with me … and I do a lot of ab exercises which is actually useful for a circus performer but probably way too many.

A couple of years ago, we did a three-person clowning pole act on a 9-metre pole and we were in a 40-degree room in suits… and when we tested, the pole was moving and it was quite slippery, so I fell [in the test] … The following night, I had these weird dreams that I was in a cafe drinking coffee and the pole was always behind me, and that has happened with other shows.

The type of works you do are very physical and high-risk. Do you think you’ll still be doing it in 10 or 15 years? Do you expect there to be changes to your practice?

I think there will be modifications… But some women who train here are in their 50s, there was [a woman] who stopped last year at 63 because she found that she was losing muscle mass which comes with old age… but this is what I've done for years so there's affects with that and it'll change what I do.

But I can't imagine not doing it.

What other parts of the arts industry do you engage in, apart from being performer and artist?

I often work backstage… I did stage managing for a while many years ago, I've done special effects work and costume stuff and prop making. I still do as required on an ongoing basis because there is not a lot of money. I also support other people by volunteering in shows.

Would you consider that part of your arts practice or something separate?

Part of all arts practice, definitely. And I also think promoting and grant writing and festival applications and showreels and videos and all that stuff are part of arts practice.

Finally, as a summary… if you were to divide your arts practice up into segments, what would it look like?

It would be 70-80% rehearsing and training, 10% actually performing and the rest is administrative and logistical work.